What if, by touching the screen of your phone, you could feel the texture of a fabric or the roughness of a stone? This is one promise of the research conducted by Vincent Lévesque, a professor at the École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS). Professor Lévesque’s work focuses on programmable haptics—a collection of technologies that stimulate our sense of touch.

When the virtual becomes tangible

Haptics is already everywhere in our daily lives: the vibration of a phone, the resistance of triggers on a game controller, the steering wheel that vibrates to signal a lane departure. But for Vincent Lévesque, these are limited uses. His research aims to explore the full potential of digital touch to enrich our interactions with technology, whether for the general public, people with visual impairements, or virtual reality professionals.

Vincent Lévesque and his research team are designing interfaces where the physical world blends with the virtual. For example, on a touchscreen, you could feel a slight click when you press a button, or perceive the texture of a surface without having to look at it. In a car, haptic feedback could guide fingers on a dashboard without having to take your eyes off the road. “The idea,” explains the researcher, “is to bring the physical world back into our digital applications.”

Creating tactile illusions

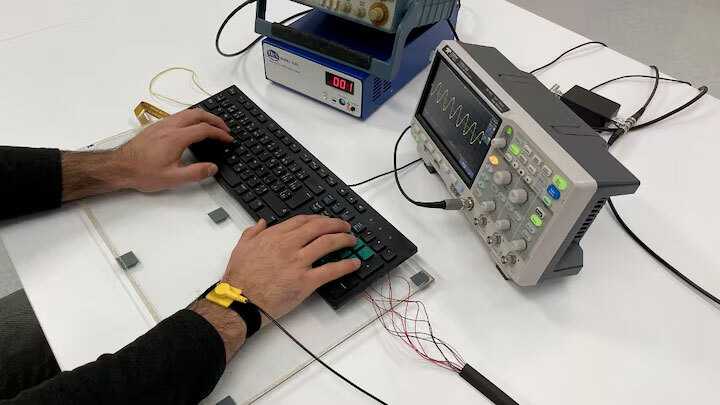

To achieve this, Vincent Lévesque and his students are developing prototypes capable of simulating touch using various processes: vibrations, friction variations, and even ultrasound. Among the technologies being explored, electrovibration is key. It consists of generating sensations of textures on the surface of a screen by modifying the friction between the finger and the glass. As a result, you could distinguish by touch a button, a slider, or even a textured path on a tablet.

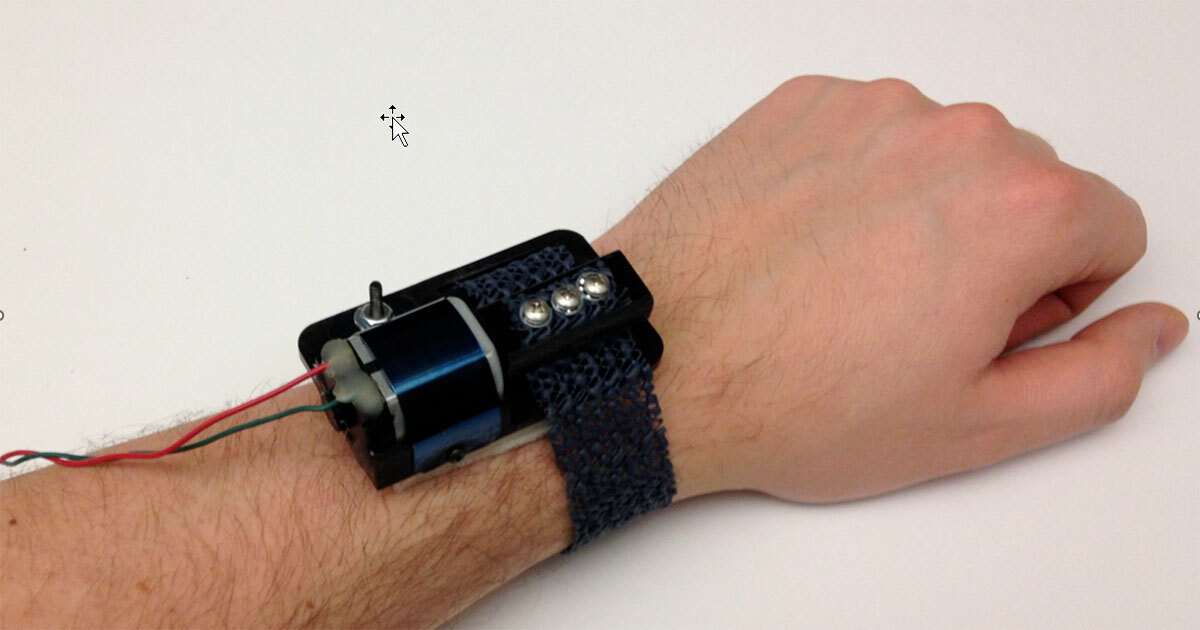

The researchers are going even further by combining several devices to create complex haptic illusions. For example, in a virtual reality game, a player who lifts Thor's hammer, struck by lightning, first feels a vibration in the controller, then a second one in their smartwatch, and finally a third one in their backpack. The effect? A feeling that the discharge is actually passing through our body. Tests conducted with players show that these sensations enhance immersion and increase enjoyment in gaming.

Haptics, a path to accessibility

The applications of this research go beyond entertainment. As part of a project designed for people with visual impairments, textures programmed onto a screen or a table guide the fingers toward objects or convey information without the need for sight. In another project, an ultrasonic plate creates pressure zones on the skin: by running your hand over it, you can “feel” tactile signals without wearing gloves or devices. The team is also exploring intuitive navigation on foot or by bike: a watch and a phone vibrate in succession to indicate when to turn left or right, eliminating the need to look at a screen.

Towards ubiquitous haptics

According to Vincent Lévesque, we are entering an era of ubiquitous haptics: a time when common objects (watches, phones, keyboards, work surfaces) will naturally incorporate tactile feedback. Haptics could blend into our environment—ubiquitous but discreet, much like modern computing. However, this vision raises challenges. “Simulating touch involves mobilizing the entire body,” explains the researcher. Unlike sight or hearing, which are perceived by a single organ, touch involves the skin, muscles, and joints. Furthermore, existing devices do not communicate well with each other yet. Software tools capable of coordinating watches, phones, tablets, and other connected objects need to be created.

A quiet revolution

Vincent Lévesque's research also aims to demonstrate the added value of haptics and convince companies to invest. The results could transform several sectors: video games, augmented and virtual reality, automotive, healthcare, and connected objects. “Haptics makes our interactions with technology more tangible,” he summarizes. “It literally gives us back the sense of touch that digital technology has taken away from us.”

Vincent Lévesque's work outlines a future where digital technology will no longer be confined to being seen or heard: it will also be felt at our fingertips.