The Turkey in the Room

Purchased on Gettyimages.com. Copyright.

Life Cycle Assessment

Did you know that food accounts for 28% of Canada’s personal carbon emission? This is higher than the global average of 26%. But not all foods are equally carbon-intensive. Some foods, particularly meat and dairy, emit much higher levels of greenhouse gases than plant-based alternatives. Animal-derived foods also require more land to produce, which contributes to the continuing loss of habitats for wild plants and animals. And while the planet continues to warm due to ineffective policy and lack of political consensus, food remains one of the key components to change, which lies very much in the hands of individuals in the global north.

Environmental footprinting methods like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), allow environmental scientists to estimate the potential of lifestyle choices to impact global warming, biodiversity loss, and water pollution. In an LCA, we create an inventory of environmental impacts linked to the flow of resources along a supply chain. For example, it can capture the extraction of mineral fertilizers and pesticides, energy, and water used in a farming operation; materials used in packaging; fossil fuels used to transport farmed products to consumers, including the energy to refrigerate and cook the food and, finally, the energy to transport waste to landfill or recycling centers. Many of these activities are obscured from the consumer’s view, but with LCA the entire environmental footprint of the foods we eat can be estimated. With this knowledge, we can make ecologically informed choices and become more sustainable in our daily practices.

Christmas Food: A Higher Impact

With Christmas approaching many people around the world will be celebrating by eating richer and more environmentally burdensome foods. Researchers at École de technologie supérieure and McGill University (in Montreal, Canada) estimated the relative environmental impacts we can expect from typical Christmas foods, along with some lower-impact alternatives.

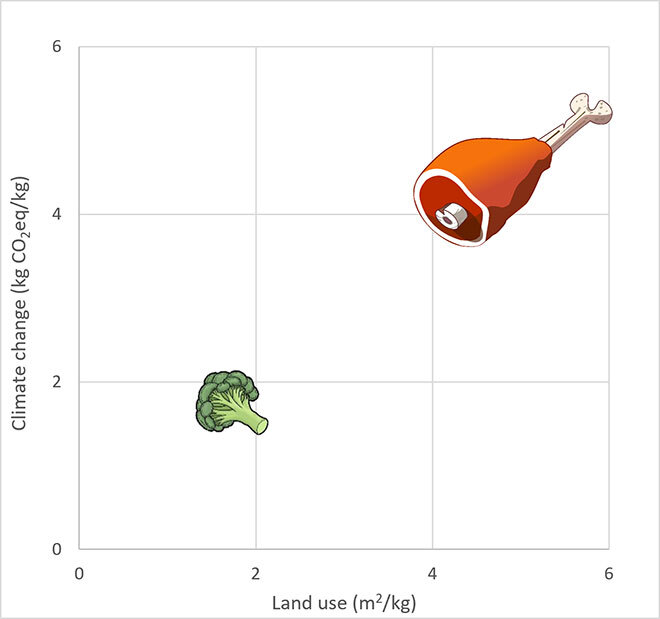

First, we assessed an average Canadian diet, which emits 15 kg CO2-eq per day while needing 16 m2 per day of agricultural land to produce that food. Vegans or people on plant-based diets emit 5 kg CO2-eq per day, and require around 5 m2 per day of land. If we look at impacts per kilogram of food, the average diet requires 4 kg CO2-eq and 5 m2 per kg of food, versus 2 kg CO2-eq and 2 m2 per kg of food for vegans.

Climate change and land use footprints of average and vegan diets

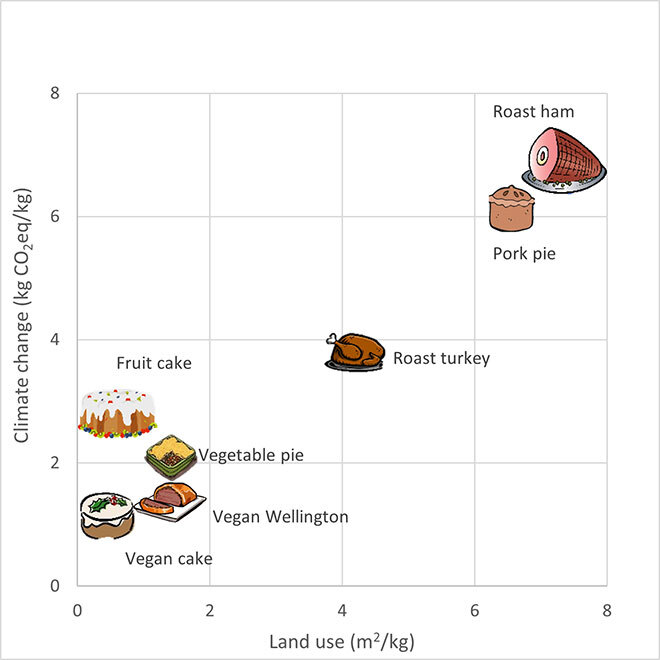

We then considered the festive foods people eat during Christmas, such as roast ham, turkey, pork pie, and fruit cake. We also considered a vegan roast Wellington, a vegetable pie, and a vegan Christmas cake. The internet is awash with interesting vegan Christmas recipes.

Climate change and land use footprints of Christmas foods

The roast ham and pork pie have much higher impacts than the entire daily average for a person eating a typical Canadian omnivore diet, confirming that the foods people eat during Christmas increases our environmental footprints. Carbon footprint and land use rise together; more land used generally means more greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, the roast ham emitted more than 3 times the carbon than the vegan Wellington and used more than 4.5 times the land area. In fact, the roast ham has the highest carbon and land use footprints out of the meals we modelled, demonstrating the carbon and land intensity of pork. Pork pie followed by roast turkey were next, trailed by the foods that do not contain meat. The vegan Christmas cake, for example, generates less carbon and used less land than the vegetarian fruit cake that contained eggs and butter.

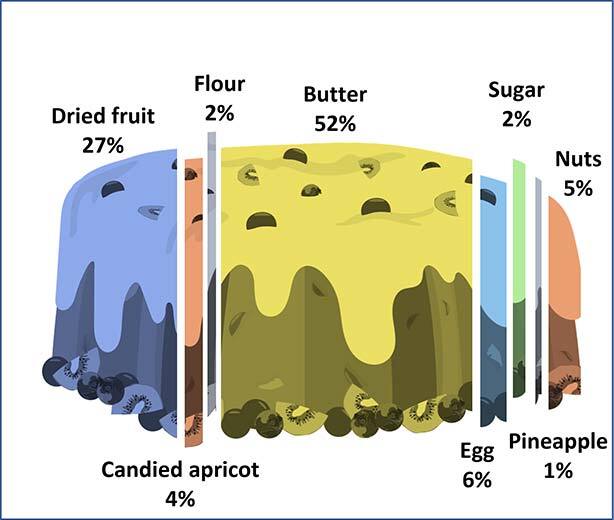

Fruit cake

Climate change contribution per ingredient

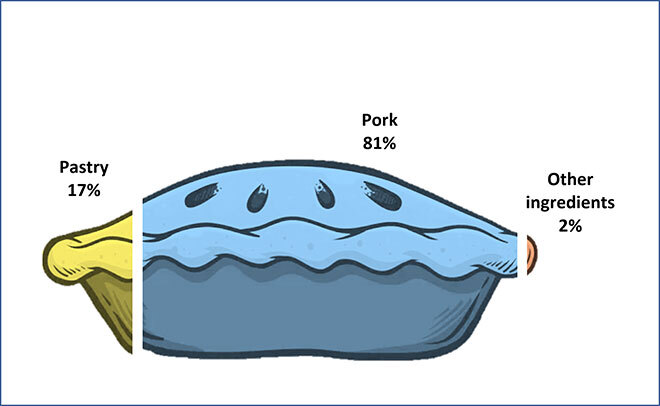

Digging deeper, the pork is 54% of the pork pie by weight, but represents 81% of its greenhouse gas emissions.

Pork Pie

Climate change contribution per ingredient

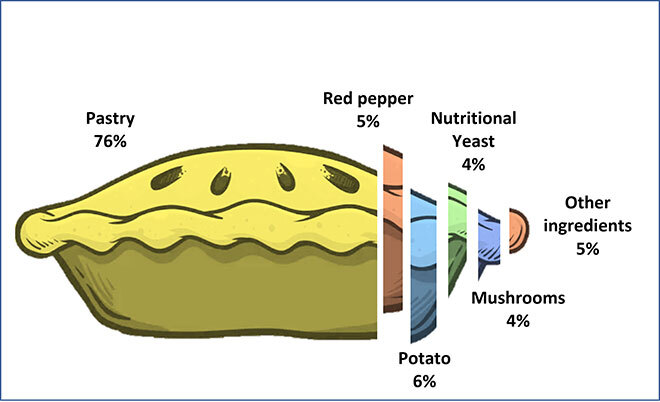

Meanwhile, the vegan pie, which is two-thirds less environmentally intensive than the pork pie, generated more than three quarters of its impacts from the pastry crust. Its contents of potatoes, mushrooms, and tofu have very little environmental impacts by comparison.

Vegan pie

Climate change contribution by ingredients

The Future Hinges on Our Personal Choices

Looking to the future, the global citizen will need to contribute no more than 2.9 tonnes of CO2-eq per year to meet the 1.5°C Paris agreement threshold. This is equivalent to around 8 kg CO2-eq per day, for all goods and services, including food. In terms of servings from our Christmas dishes, one portion of glazed roast ham already uses half of a sustainable daily carbon budget. A combined meal of a serving each from the roast ham, pork pie, and fruit cake would tally around 70% of an individual’s daily carbon budget, leaving only a small allocation for all other activities such as heating, transport, and gifts from Santa. On the other hand, a person who ate a serving each of the vegetable pie, vegan Wellington, and vegan cake would only use around 14% of their daily carbon budget, and a fairly small parcel of land.

There are many choices individuals can make to decrease their carbon or land footprint, but food is one of the most important. At Christmas time when we tend to eat more and richer foods, it pays to keep in mind how much our choices take from the planet and to become aware of the environmental benefits of delicious plant-based alternatives. You can read more about how we model carbon footprints of food and cities in the papers below.

Related papers

Elliot, T. (2022). Socio-ecological contagion in Veganville. Ecological Complexity 51, 101105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecocom.2022.101015

Elliot, T. & Levasseur, A. (2022). System dynamics life cycle-based carbon model for consumption changes in urban metabolism. Ecological Modelling 473, 110110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2022.110010

Goldstein, B. et al. (2016). Surveying the Environmental Footprint of Urban Food Consumption. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21, 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12384.