Human beings generate heat as a by-product of converting chemical energy from the food we eat into metabolic energy. For building engineers, predicting the amount of heat that humans will generate in a space is essential to correctly design heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, thus creating comfortable and energy-efficient indoor environments.

The heat produced in our bodies increases when we are active (running, playing, even walking), and it must be balanced by equivalent heat loss in our environment so that our bodies can maintain a stable temperature. This means we can predict the amount of heat generated by the occupants of a room based on the number of people present and the type of activity they are doing. But how exactly is this heat lost by the human body?

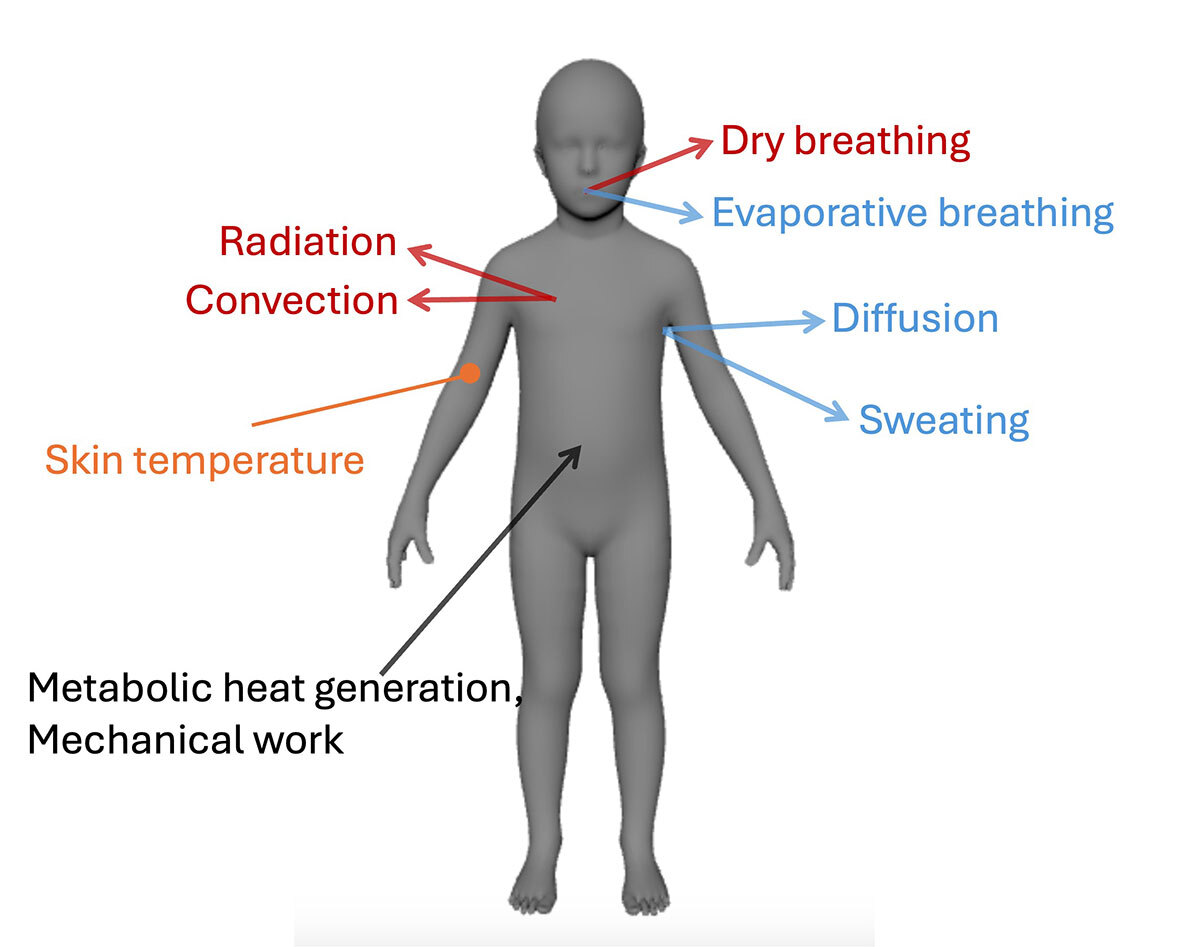

The human body loses heat through two media: through the skin and through breathing. Each of these media involves two modes of heat transfer: “dry” and “evaporative.”

Dry Versus Evaporative Heat Loss

Dry heat loss refers to heat lost due to a difference in temperature between the body and the surrounding environment. For example, when our skin is warmer than the surrounding air, our bodies lose dry heat through convection, meaning that the cooler surrounding air comes into contact with our warm skin and cools it down. We also lose dry heat through breathing, as warm air from our lungs mixes with the cooler air in our surroundings when we exhale.

Evaporative heat loss is due to the evaporation of water from our bodies. Water vapour continually passes through the pores in our skin by diffusion, and the air we exhale also contains water vapour. When we sweat, liquid water permeates through the open pores of our skin and then evaporates, further cooling our bodies. Figure 1 represents this mechanism and the terms used for each type of heat loss.

Different categories of air-conditioning equipment can handle different ratios of dry heat vs evaporative heat. For example, a baseboard heater only supplies dry heat and does not remove or add humidity to the air, while an air-conditioning unit can provide both cooling and dehumidification. Therefore, understanding the ratio of dry heat loss to evaporative heat loss from occupants is essential to select the proper heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system for a space.

Children Are Not Just Small Adults

Many models exist to estimate heat loss in adults. However, children have different heat loss mechanisms than adults. For starters, young children are smaller and weigh less than adults, so they release less heat while doing the same activity. Second, they have a higher body surface area to weight ratio, which allows them to lose heat more efficiently through convection and radiation at the skin level. Most importantly, prepubescent children have underdeveloped sweat glands, which limit their ability to cool down through sweating. This means children’s ratio of dry to evaporative loss will be different from that of adults doing the same activity. These differences mean that applying adult-based models to children can lead to inaccurate predictions of heat loss, comfort and safety.

To address this gap, we developed a child-specific steady-state heat balance model for the prediction of heat loss in children. We began by revisiting the fundamental thermodynamic equations that describe the heat exchanges shown in Figure 1. Child-specific factors such as body weight, height, surface area, metabolic heat generation rate, and breathing rate were incorporated to reflect realistic physiological conditions of children.

Historically, sweating has been modelled using regression equations developed by Ole Fanger on data from experiments conducted on adults in the 1970s. We adopted a similar empirical approach. We conducted an extensive review of previous studies that measured sweat rate, skin temperature, metabolic heat generation, and environmental conditions (air temperature and humidity) in children and adults during various physical activities. Statistical analysis of this data allowed us to develop regression equations to predict sweat-related heat loss in children under 18 and prepubescent children. Combined with modified equations for other modes of heat transfer, we now have a comprehensive, child-specific heat balance model.

Impacts on HVAC Design

The most important outcome of this research is that the new model enables HVAC engineers not only to predict heat given off by children, but also their specific ratio of dry to evaporative heat for a variety of activities. This way, HVAC engineers can use realistic data to design heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems better suited to children's environments, such as schools and daycares. This data can help engineers accurately calculate the amount of cooling, heating or dehumidification required to maintain comfort. It can also help researchers quantify more accurately the heat produced by child occupants, supporting the growing body of research on children’s thermal comfort and indoor air quality in classrooms.

Additional Information

For more information on this research, please read the following paper: Farah Youssef, Stéphane Hallé, Katherine D’Avignon, Modeling heat loss through sweating: Towards improved heat load prediction from child occupants, Energy and Buildings, Volume 342, 2025, 115888, ISSN 0378-7788.